Story Without End?

Found Footage in the Digital Era

Tilly Walnes

The footage now at our disposal is so great and rich a store that no one can say, “These are its limits". And one would have to be extremely foolish to say, “These are the limits of its uses” – either in content or method. Artists who have worked with these materials have surprised us so often with what we thought was familiar and worn that we may be sure that, as long as artists continue to work in this form, there is no end to its newness.

- Jay Leyda, Films Beget Films, 19641

A survey of online video-sharing websites such as YouTube and Google Video reveals a flourishing culture of “mash up” films. These are contructed by appropriating, decontextualising, and reworking a diverse range of moving image material, such as advertisements, music videos, movie trailers, and news footage, to produce new work. The resulting films often critique the mass media’s use of images, narrative codes, and editing conventions, exposing their ideological function and questioning their authority as conveyors of meaning. To take one example, Goonies of the Caribbean: The Search for One-Eyed Willie intercuts scenes from The Goonies and Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl to construct a fake film preview that satirizes the structural similarities of film trailers and the thematic likeness of the two component films.

Recycling pre-existing moving images to construct an irreverent collage has a long history in found footage filmmaking,2 beginning with Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart in 1936, which stitched together and slowed down movie reels featuring the eponymous actress and added a blue filter and samba soundtrack. Later, in 1958, Bruce Conner’s A Movie mixed feature films, newsreels, soft-core porn, and leader tape. The advent of electronic video, more manipulable than celluloid, facilitated the sampling and repetition of found images and sounds, including those recorded from television. For example, Dara Birnbaum’s influential Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978-9) elides narrative to deconstruct the representation of a fantasy figure, while Gorilla Tapes’ The Commander in Chief (1985) remixes footage of speeches by Ronald Reagan to expose the belligerent nature of his foreign policy.

Making moving image compilations on a computer is arguably just the latest phase in this historical continuum. Yet the shift from analogue to digital technologies of distribution, exhibition, and (post)production opens up radical new possibilities for found footage filmmaking. This article will assess the impact of digitality upon the practice, taking as its premise the essential conception of found footage filmmaking as a dual process involving 1) the appropriation of pre-existing moving images and 2) the reworking of that material to create a new work. As I shall argue, the processes and techniques of sourcing and modifying moving image material digitally not only permit new developments in the practice, but also problematize the notion of the found footage film as it has been traditionally conceived.

Appropriation

The history books tell us that Esfir Schub's research and acquisition of source material for found footage filmmaking has been a time-consuming process, requiring persistence and chance. Thumbing through scores of outdated catalogues was met with resistance by archive curators, thus Scrub eventually discovered suitable footage rotting in rusty cans in a cellar3 while Bruce Conner searched through thrift shops, and Craig Baldwin scavenged cut-offs from editing room floors and film laboratory bins.4

The advent of new technologies of distribution has had a major impact upon the appropriation of source material required for found footage filmmaking. Digitized media can be reproduced and circulated with ease and at relatively little cost. The growth of online data storage capacity coupled with accelerated connection speeds has made the Internet the ideal space for storing digital video, providing easy access to a global network of images and sounds. These hardware advancements, in tandem with recent developments in software technology - such as sophisticated compression codecs, streaming media, and Flash - have enabled access to a broad range of material for reuse by an increasingly technologically confident audience.

A wide range of films are centralized and readily available from websites such as the Internet Archive, which holds 140,000 digitized films in the public domain. Educational and industrial films, cartoons, trailers, feature films, and news footage can be legally downloaded and reworked by the public for non-commercial use. Indeed, such use of the material is actively encouraged, with examples showcased on the website, including Panorama Ephemera (2004), made by one of the archive’s own collectors, Rick Prelinger.

Although its advocates have tended to refer to found footage filmmaking as a no-budget folk art, open to everyone, it has always been somewhat restricted to those who could gain access to filmstrips and to expensive editing equipment – people such as Schub and Baldwin, who were working in the industry already. Today, with video sources, editing programs, and tutorials freely available online, the practice is arguably more widely democratized and truly participatory. As a statement on the Internet Archive explains, “By providing near-unrestricted access to these films, we hope to encourage widespread use of moving images in new contexts by people who might not have used them before".

The Internet, then, constitutes a new kind of archive, one that offers unparalleled access to a huge range of material and which sustains a community which values and encourages creativity. This aspect has been bolstered by Creative Commons, a licensing initiative established in 2001, whose emergence offered a compromise to the polarized rigidity of the existing options: “all rights reserved” or “public domain". Creators wishing to upload their videos, music, images, and writing can choose between six licenses, each with different sets of permissions specifying the parameters within which others can use their work, such as whether the results can be used commercially or to create further derivative works. 51,787 of the titles on the Internet Archive are films uploaded by the public under such licenses.

The Creative Archive is a UK initiative in the same vein, established in April 2005 by the BBC, the BFI, Channel 4, and Open University. It has a single license based on the model of Creative Commons to which the public can sign up in order to download stills, audio, and moving image clips from the archives of the member organizations. This material can then be remixed and manipulated for non-commercial use, provided that users credit their sources and share their derivative works with others in turn. From the point of view of the BBC, as a public service broadcaster the Creative Archive is a convenient method of allowing its license fee payers access to their archive, more in tune with current technology than on-site viewing of video tapes.5 The BBC has contributed historical and natural history footage6, the BFI has made available material such as archive newsreel and silent comedy, and Channel 4 has a section of useable documentary rushes on its mini-site FourDocs.

Because [accessing work from the Internet] is so easy, it is possible to explore far more ideas than in the traditional archive/library situation, and thinking is a lot freer whereas many librarians and archivists are far too paranoid and protective, fearing that use of content equals loss rather than gain...8

The buy-in from organizations such as the BBC is symptomatic of a shift in the understanding of the archive, models of distribution, and ownership of images, engendered by the advent of the Internet and its principles of exchange and user-generated content, as well as, presumably, its threat to traditional broadcasting models. According to Paul Gerhardt, the Strategic Director of the Creative Archive at the BBC, the original intention of the project was to facilitate public access to their archive for viewing purposes, but they soon realized that the technology was more suited to sharing than simply broadcasting. The BBC reiterates the notion of the public as users rather than consumers:

We look forward to a future where the public have access to a treasure-house of digital content […] which the public own and can freely use into perpetuity. A future where the historic one-way traffic of content from broadcaster to consumer evolves into a true creative dialogue in which the public are not passive audiences but active, inspired participants.9

Furthermore, with digital media, the final work is equally manipulable and exchangeable. Creative Commons and Creative Archive licenses encourage users to make their derivative works available for further recycling by others. Bennett of People Like Us does likewise, posting her films back on the Internet. In fact, she made Resemblage(2004) by mixing films by found footage luminaries such as Larry Jordan and Stan Vanderbeek, together with her own previous film We Edit Life (2002), resulting in a meta-collage. 10 The practice of recycling no longer ends with the derivative work but can be perpetuated, with found footage filmmakers feeding their own work back into the chain for further circulation and manipulation.

Traditionally, a key aspect of the practice is that the source material has been discarded by the industry and subsequently salvaged by the found footage filmmaker who reinvests it with value. The pamphlet of a touring theatrical program, entitled “Junk Aesthetics", proclaims, “By now several generations of individual film artists have been creatively looting and pillaging the ‘junk’ bins of the film industry, cutting room floors, and second hand shops".11 Detritus.net, a website about recycled culture, states in its manifesto:

Our society spends a lot of time telling us that there is some brand new, fresh cultural produce, generated from thin air and sunshine, slick and clean. They package it with pretty plastic & ribbons and then feed it to us. A lot gets thrown away: the ribbons, the wrapping; culture becomes garbage, or it dies, and rots behind the refrigerator. But the new fluffy shiny stuff still gets churned out, and it gets forced between our teeth. And we are told to swallow it. We will not swallow. We will chew, and then spit. We will play with our food, and create something new and interesting from it.

Craig Baldwin proudly declares, “My ‘archive’ comes mostly from dumpsters. Refuse is the archive of our times […] It’s a test of our ingenuity to take that material (from the trash) and redeem it, so to speak: to project new meanings into it".12

Today, the idea of a filmmaker rescuing a potential gem from incineration, preferably finding it in a can covered in cobwebs, is rendered almost quaint by the availability of online material. Anyone with access to the Internet can download digitized moving images with a few clicks of the mouse. Themes or subject matter can be selected using keywords and categories both on the websites holding them and on searchable catalogues and directories of public domain films available elsewhere on the Internet, such as The Public-Domain Movie Database, OpenFlix, and MoviesFoundOnline. A film that has been specially selected to be digitized and uploaded to the web has been accorded value and arguably loses its status as “junk". Certainly many films available online are obscure and rarely seen: for instance, the A/V Geeks Film Archive, made available through the Internet Archive, includes titles such as "Fish Family A," about the reproductive cycle of the blue acara fish, and “Check the Neck", an instructional film for policemen on resuscitating a person whose larynx has been removed. A/V Geeks’ founder, Skip Elsheimer, recovered the films in his collection from second-hand shops, bins, and school and government auctions. On the website he explains, “These films were regarded as obsolete and useless by the state, who would take anything to get rid of them. If I didn't get them, who knows where they would have ended up - a dumpster, maybe?” The film corpus on the Creative Archive websites, by contrast, has been purposefully curated, and arguably sanitized. The BFI collection, for instance, currently features a mere 27 titles, including old favourites such as Daisy Doodad’s Dial 13 and The Little Match Seller, 14 titles that the BFI distributes to cinemas and screens to paying audiences – in other words, hardly refuse.

Online archives have had an impact on another common feature of found footage filmmaking: rebellion. Much recycling of moving images is politically charged and foregrounds the objective of resisting and undermining the ownership of media, whether by a company or an archive, by taking material without permission and “turn[ing] the barrage of images back on itself".15 Baldwin considers found footage filmmaking to be a movement that “talks back, is sarcastic, has an attitude, steals your images, and all that kind of thing. Punk kind of attitude".18 Some films explicitly reference this subversiveness in the content of their work. Negativland and Tim Maloney’s Gimme the Mermaid (2002) combines sequences from Disney animations with an answering machine recording of a music industry lawyer aggressively threatening to sue the artists for copyright violations. The Artwork in the Age of Mechanical Reproducibility by Walter Benjamin as Told to Keith Sanborn © 1936 Jayne Austen (1996) insolently compiles a number of copyright violation warnings taken from the beginnings of VHS tapes and DVDs, and A Fair(y) Use Tail (Eric Faden 2007) irreverently takes advantage of the principles of “fair use", a rule which allows use of copyrighted material for educational purposes, by explaining the concept of copyright using clips from 27 films belonging to the notoriously litigious Disney corporation.

Reworking

Beyond appropriation, digital technologies are strongly affecting the second procedure involved in found footage filmmaking – reworking – both editing as a process and the resulting aesthetic.

A found footage filmmaker employing non-digital editing processes on a reel of celluloid film must either make back-up copies of all source material or risk working on a single print, with any mistakes requiring a painstaking process of disassembly and reassembly, and physical alterations to the surface of the celluloid being often irreparable. With analogue video, segments to be compiled must be assembled into a fixed order to be copied onto a master tape - any changes to the order or length of the resulting sequence necessitates re-recording all subsequent images from the point of the change.17 The reproducible nature of digitally-stored media objects and the recent development of increasingly sophisticated editing tools simplify the processes of selecting and combining sequences of moving images and manipulating individual images. Stored as digital information, the original work can be revisited by the editor over and over again, and computerized non-linear editing makes changing the order of the shots easier - if one part of the sequence is changed or deleted, the other sections will move to accommodate it. This new way of organizing sequence has had a profound effect on the type of work that can be produced.18 Filmmakers and editors have more flexibility to experiment.a) Process

Films by People Like Us reference the ease of sampling that were involved in their construction. We Edit Life opens with a discussion between two people about using a computer to change the color of a filmstrip. The voiceover contextualizes the scene: “Experimenters in visual perception are using computers to create weird, random patterns that never occur in real life". In The Remote Controller, which concerns the ease of using computerized machines and pushing buttons, the voiceover declares, "Mixing is so simple a child can do it".

The result is breathtaking beauty and lasting good taste". The child’s play motif recurs in both Story Without End and Trying Things Out, in which children position and reposition toy buildings on a town map and a stage setting respectively, echoing the constructive work of found footage filmmaking.

Digital editing tools have not only simplified the tasks of cutting and assembling moving images, but have also made the processes themselves standardized functions of the operating system. This development has two implications for found footage filmmaking. Firstly, many found footage filmmakers have conceptualized their work as a sculptural craft, its specificity lying in the notion of a filmstrip not as a homogeneous, finished text to be respected but as the raw material with which to play around and create a new work. Craig Baldwin describes his awareness of the materiality of the films playing in the (porn) cinema where he worked as career-defining:

I would see the films again and again and again from about three feet away. I would be totally demystified. I knew what film was – it was a piece of image, you know, chemicals on celluloid. I had much more of a plastic, or collage, or more of a visual art approach to it, and I just played and mucked around with it, cutting and pasting it.19

With cut and paste functions now integrated into digital video editing technology, intervening into the filmstrip and constructing a media object from pre-existing parts have been conventionalized, or as Lev Manovich puts it, new media “legitimizes” these processes. While Manovich may be exaggerating when he asserts that “pulling elements from databases and libraries becomes the default; creating them from scratch becomes the exception",20 this way of working which seemed so radical in the pre-digital era is now widespread, calling into question the formal distinctiveness of found footage filmmaking practice. Secondly, playing around with one of a (hypothetically infinite) number of copies of a film, with tools that allow an unlimited number of changes to the edit and which still leave the original work intact, removes the subversiveness of the gesture of taking a splicer to a physical, unique filmstrip, massacring what may be the only print of someone’s work. Thus, at the same time as digital technologies simplify the process of reworking moving images, they also problematize some of the defining characteristics of the practice of found footage filmmaking.

b) Aesthetics

Celluloid footage can be reworked in a number of ways. Shots from a single film may be reordered so that they are read in a different way, or sequences from a number of films may be edited together, such as in Conner’s A Movie. The original film may be transformed by working directly on the material, by painting or scratching the celluloid, to create a filmic palimpsest in which the original shows through. For example, Len Lye painted and stencilled on discarded documentary material from the GPO Film Unit to make Trade Tattoo,21 and Cathy Joritz irreverently scratched beards and devil horns over 1950s footage of a lecturing psychologist in Negative Man.22 The advent of electronic video editing equipment from the early 1980s onwards has allowed images to be mixed within the frame, distorted, and multiplied, such as in Jean-Luc Godard’s video collage Histoire(s) du cinema. 23

Digital editing software expands the range of techniques that can be applied to treat found material. In Obsessive Becoming, Daniel Reeves mixes found footage, photographs, and newly recorded material, using techniques including layering, morphing, and flipping over images, bleaching out color and backgrounds, inserting frames within frames, employing paintbox effects, animation, and slow motion.24 Reeves recognizes how the evolution of editing technologies has enabled different types of imagery to be produced:

The learning curve of the software – the morphing programs, the compositing programs – was very steep. I would pour through magazines to see month by month what was happening […] With Obsessive Becoming it wasn't five years in production - it was probably ten years because I started in '85 with my first Amiga, and it wasn't till '93 - almost '94 - when I finally went ‘Aha!’ This is the dream world that I wanted to get to. To be able to tear an image apart and re-form the image with complete freedom. 25

A mini history of these emerging possibilities is evident in the work of The Tape-beatles, from Matter, 26 which features a triptych of frames of found footage, to Good Times, a similar piece which features up to twelve frames at a time. As the voiceover in the latter work confirms, speaking over apposite images of a food blender and factory assemblage, “And now these uniform interchangeable parts can be put together quickly, saving a great deal of time and money". Pushing the number of frames within a frame almost to its limit, Mosaik Mécanique features the 98 shots from the Charlie Chaplin film A Film Johnnie, assembled into a spatial patchwork in which they are shown simultaneously on loop.

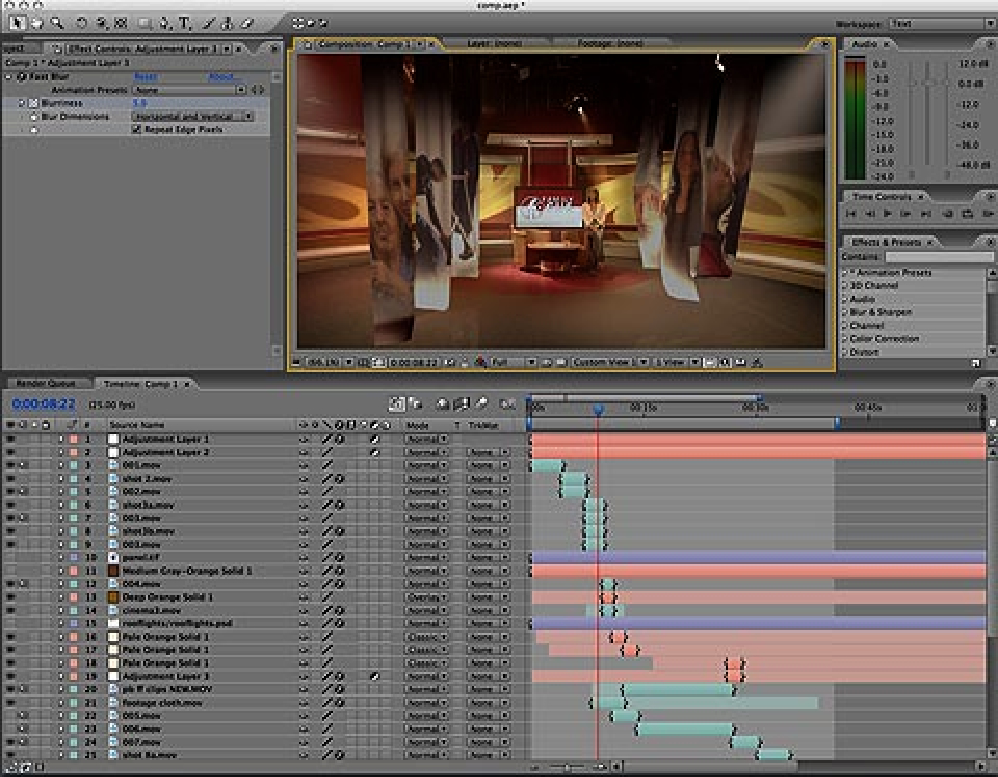

The juxtaposition of images within the frame, not only in sequence, is one of the most striking characteristics of recent digitally constructed found footage work. Manovich labels this practice “spatial montage".27 Whereas montage nearly always operates in the temporal form in twentieth century cinema, the capacity for spatial montage is vastly increased in the digital era. In contrast to the filmstrip’s linear arrangement of discrete images of equal size, designed to be shown in sequence, computer editing adheres to a spatial logic, the screen being divisible into an array of pixels which can easily be moved from one location on the grid to another. Digital compositing software, such as Adobe’s After Effects, introduced in 1993, allows the user to construct an image by combining an almost infinite number of layers, each of which can be added, deleted and manipulated separately. As Manovich argues, “the diacronic dimension is no longer privileged over the syncronic dimension, time is no longer privileged over space, sequence is no longer privileged over simultaneity, montage in time is no longer privileged over montage within a shot".28

While Manovich mainly discusses the shift towards spatial montage in reference to Hollywood feature films and other live action films, I propose that this development is particularly radical for found footage filmmaking. It is precisely montage which endows found footage films with their meaning. Found footage film’s conflict of images in time is “a subversive realization of Eisenstein’s theory of dialectical montage": the thesis and antithesis of shot and counter-shot are particularly conflicting when taken from disparate sources.31 Spatial montage facilitated through digital compositing introduces a new type of associative process. Objects and figures are recontextualized in unlikely environments, associations are made between images sat shoulder to shoulder. Digital compositing thus opens up a whole other dimension of possibilities for montage, one which is arguably more immediate, yet at the same time more overtonal, than a temporal clash of images.

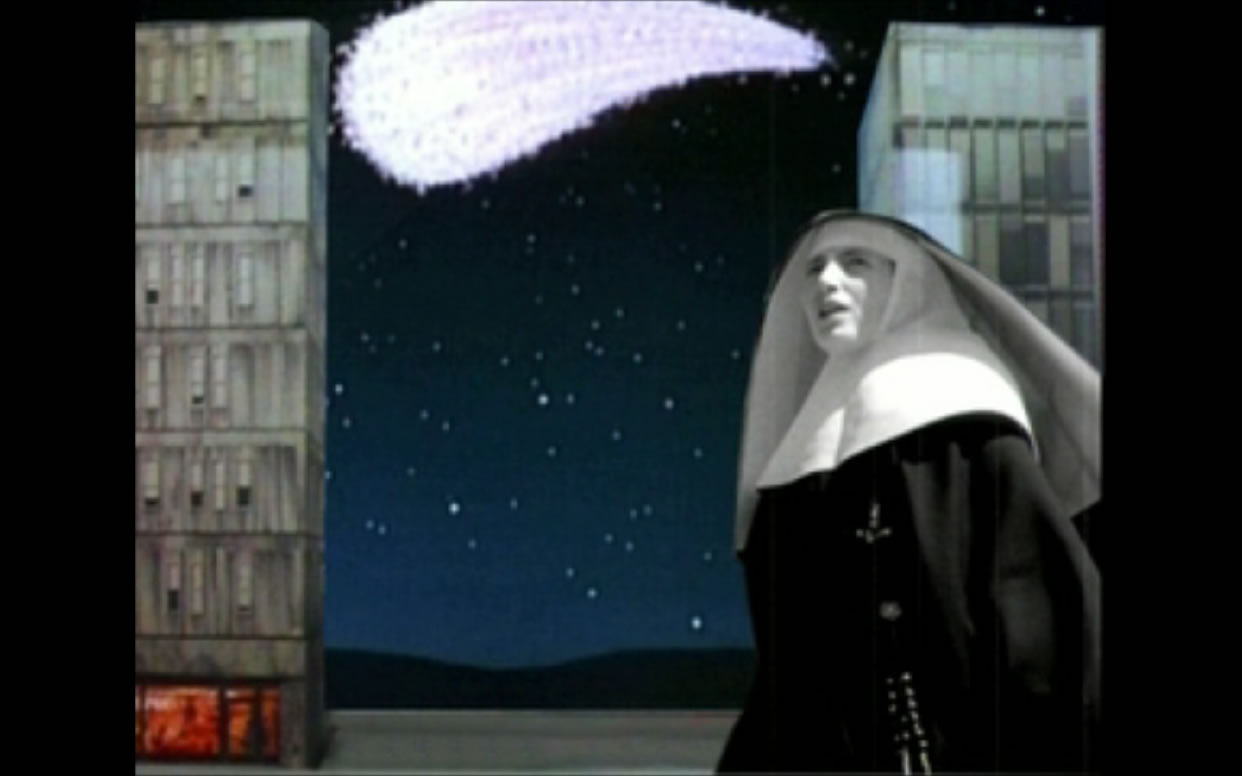

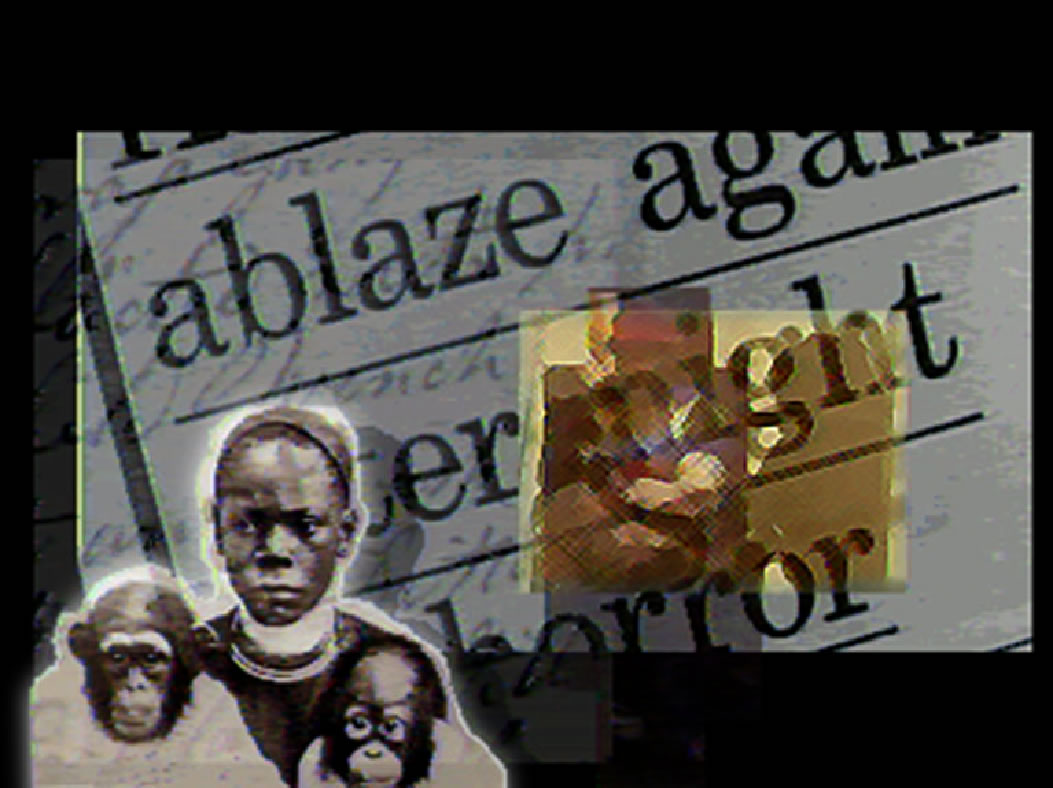

In Go West Young Man, Keith Piper spreads out, juxtaposes, layers, and overlaps archived moving images, photographs, and newspaper cuttings across the frame in an attempt to map out and thus negotiate the history of the exploitation of black people.32 People Like Us intricately interweaves fragments of archived moving images – people, objects, backdrops - so that they appear to be interacting within the same spatio-temporal location, with no apparent boundaries between them.

If cinematic montage joins elements consecutively and collage brings them together contemporaneously, how do the two systems and their different directionalities work together? Taken separately, theories of spatial collage and linear montage are inadequate for describing the effect produced when the two are combined - this requires a different understanding.

Yvonne Spielmann argues that when digital compositing is combined with linear editing, producing what she calls a “cinematic cluster", the spatial dimension dominates. In her words, “the overriding linear structure of moving images is reversed into spatial density".34 I do not fully accept Spielmann’s argument that spatial organization counteracts linear continuity as a rule. While spatial structuring does seem to take primacy in more fragmented works such as Piper’s, I am not convinced that this approach is wholly adequate to account for the films of People Like Us - frustratingly, Spielmann does not give any examples. While this type of work does not rely on shot-countershot formations, neither does it comprise static, collaged images, as Spielmann’s term “cluster” suggests. Rather, moving image collage involves a more complex bi-dimensional process. Different elements have separate timelines, carrying them over into subsequent shots at different rates, weaving in and out through both space and time. As we have seen, this aesthetic is reflected in editing software, which increasingly combines both sequential editing and compositing tools that are operated within the same window. As Manovich observes, “reordering sequences of images in time, compositing them together in space, modifying parts of an individual image, and changing individual pixels become the same operation, conceptually and practically".35 Time and space are no longer separate modes but are fully imbricated in the editing process, engendering a new multi-dimensional form of montage.

Another feature linking the digital found footage work of Bennett, Reeves, and Piper with collage is that they all incorporate a range of media. Their source material includes analogue and digital film, still photographs, drawings, engravings, newspapers, animation, graphics, and typography. Different materials can be found in analogue found footage film too: for instance, in Like All Bad Men He Looks Attractive (2003), Michele Smith attaches various elements to 35mm film, including photographic slides, magic lantern slides, plastic bags, construction blueprints, and butterfly wings. The fundamental difference is that the ability to mix media is an inherent part of the processing workflow in digital media. Digitizing media objects involves translating them into binary code, computer data represented in numerical terms as ones and zeroes. The material differences between objects are eradicated as the code from one can be added to the code from another to form a homogeneous image.36 They are no longer medium-specific, but can be “stored, accessed, and controlled” by the same equipment.37 Combining what were once different media is thus not only very straightforward but is performed almost by default. As Lessig puts it, “mixing is no longer the exception; mixing is the rule".38 Anne Everett recognizes this inherently recombinatory nature of computerized media and its binary code: she updates Julia Kristeva’s notion of intertextuality – “Every text builds itself as a mosaic of quotations, every text is absorption and transformation of another text”39 – with her own neologism, “digitextuality", to account for what we could call the hyper-recycling facilitated by digital media, with which multiple texts can be integrated seamlessly into a new one.40

Perhaps, then, the term “found footage film” is anachronistic when applied to digital work such as that of People Like Us, Reeves, and Piper. For not only is the term “film” rejected by purists as inaccurate for describing the digital moving image, “footage” itself does not quite account for the static images, animation, and all the other elements that can now easily be incorporated. This type of work could more precisely be described as “hybrid media text", or “recycled moving image collage", terms which reflect the new possibilities that are opening up in a practice no longer limited to one medium.

Conclusion

I have argued that the use of digital technologies contravenes a number of the traditionally fundamental principles of found footage filmmaking. The proliferation of moving images on the Internet renders the idea of source films being “found", discarded by the industry or otherwise, an antiquated notion, premised on the physical hindrances of analog distribution. The buy-in from media institutions raises questions about the subversive nature of the practice, limiting its critical capacity and repositioning what was formerly the domain of experimental filmmakers into the mainstream. The subversive aspect of found footage culture is further tempered by the replicability of digital media and the computerization of editing, which no longer involves the destructive act of physically cutting a filmstrip.

Taking a more constructive viewpoint, digital media also open up new possibilities for the practice of found footage filmmaking. Online archives offer access to a wide range of source material. The distinctive aesthetic of expanded space encountered in the work of People Like Us, with figures from different eras interacting within the frame, could be read as a reflection of both the excitement and anxiety of the new paradigm of distribution which is now making it possible to access a diverse range of images just a few clicks away from each other. The flexibility of the digital image facilitates recycling and recombination, and expands the options for editing and effects, including incorporating spatialized juxtapositions and bi-dimensional relationships between the elements. Moreover, new licensing and distribution models mean that the end product can be just as readily introduced back into the system for further circulation and reworking.

In the light of this evidence, a broad reconceptualization of found footage filmmaking is warranted. It now seems clear that, as Jay Leyda predicted in 1964, the increasing availability of source material and new ways of working with it enable the practice to continue to push the boundaries, keeping it fresh, albeit in a modified form.

1. Jay Leyda, Films Beget Films (London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd, 1964), 140.

2. Referred to as ‘compilation film’ by Leyda or ‘collage film’ according to William C. Wees, Recycled Images: The Art and Politics of Found Footage Films (New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1993).

3. Leyda, 24-25.

4. Baldwin quoted in Rob Yeo, ‘Cutting Through History: Found Footage in Avant-garde Filmmaking’, in Cut: Film as Found Object in Contemporary Video, ed.Stefano Basilico (Milwaukee, MI: Milwaukee Art Museum, 2004).

5. Paul Gerhardt, ‘Creative Content in the Public Domain’ (paper presented at ‘Sample Culture Now’ symposium at Tate Modern, London, 15/12/04), http://www.tate.org.uk/onlineevents/archive/d_culture/.

6. Their trial phase to establish public value ended in September 2006 and their involvement is currently under review.

7. Lawrence Lessig, ‘The Failures of Fair Use and the Future of Free Culture’, in Cut: Film as Found Object in Contemporary Video, ed. Stefano Basilico (Milwaukee, MI: Milwaukee Art Museum, 2004), 48.

8. 5th September 2007

9. BBC, Building public value: Renewing the BBC for a digital world (London: BBC, 2004), 5.

10. Resemblage was made from the following films from the LUX collection: Everywhere at Once, byAlan Berliner (USA: 1985); Myth in the Electric Age,byAlan Berliner (USA: 1981); Natural History,byAlan Berliner (USA: 1983); Once Upon a Time, by Larry Jordan(USA: 1974), Orb, by Larry Jordan(USA: 1973); Inaudible Cities, by Semiconductor(UK: 2000); Breathdeath, by Stan Vanderbeek (USA: 1964)

11. Michael O’Pray and Paul Taylor, ‘Junk Aesthetics: Found Footage Film’ catalogue (London: Film and Video Umbrella, 1986) – this program included titles by Joseph Cornell, George Landow and Martha Haslanger

12. Baldwin quoted in Yeo, 24.

13. Directed by Florence Turner (UK: Turner Film Company, 1914).

14. Directed by James Williamson (UK: Williamson Kinematograph Company, 1902).

15. Interview with Emergency Broadcast Network in Sonic Outlaws, directed by Craig Baldwin (USA: Other Cinema, 1995).

16. Interview with Craig Baldwin in Wees, 70.

17. Chris Meigh-Andrews, A History of Video Art: The Development of Form and Function (Oxford: Berg, 2006), 265.

18. Meigh-Andrews, 2006, 268.

19. Interview with Baldwin in Wees, 68.

20. Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), 130.

21. UK: 1937

22. USA: 1985

23. Switzerland/France: JLG Films/Canal +, 1988-1998

24. UK/USA: 1995

25. Chris Meigh-Andrews, ‘Interview with Daniel Reeves’ (Glasgow 21/11/00), http://www.meigh-andrews.com.

26. USA, 1998

27. Manovich, 2001, 322; NB. Manovich clarifies that editing alone does not constitute montage, but requires the filmmaker’s agency in determining the relationship between the images.

28. Manovich, 2001, 326.

29. Manovich, 2001, 155-6.

30. Adobe After Effects tutorial, http://www.mhouse-j.com.

31. Lucy Reynolds, ‘Outside the Archive: The World in Fragments’, in Ghosting: The Role of the Archive within Contemporary Artists’ Film and Video, ed.s Jane Connarty and Josephine Lanyon (Bristol: Picture This Moving Image, 2006), 16

32. UK: 1996

33. Fox, Killian, ‘Come on, feel the noise’, The Observer, 11/06/06

34. Yvonne Spielmann, ‘Aesthetic features in digital imaging: collage and morph’, Wide Angle 21.1 (1999), 139.

35. Lev Manovich, ‘What is digital cinema?’, in The Digital Dialectic: New Essays on New Media, ed. Peter Lunenfeld (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1999), 179-180.

36. Ron Brinkmann, The Art and Science of Digital Compositing (San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann, 1999), 2.

37. Peter Lunenfeld, ‘Introduction’, in The Digital Dialectic: New Essays on New Media (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1999), xvi.

38. Lessig in Basilico, 50.

39. Quoted in Anne Everett, ‘Digitextuality and click theory: theses on convergence media in the digital age’, in New Media: Theories and Practices of Digitextuality, ed.s Anne Everett and John T. Caldwell (London: Routledge, 2003), 6.

40. Everett, 7.